The following selection of photographs from the last three years of Fraction Magazine will be on exhibit at the

Rayko Gallery in San Francisco from August 11 to September 20.

Please join us for the opening on August 11.

From David:

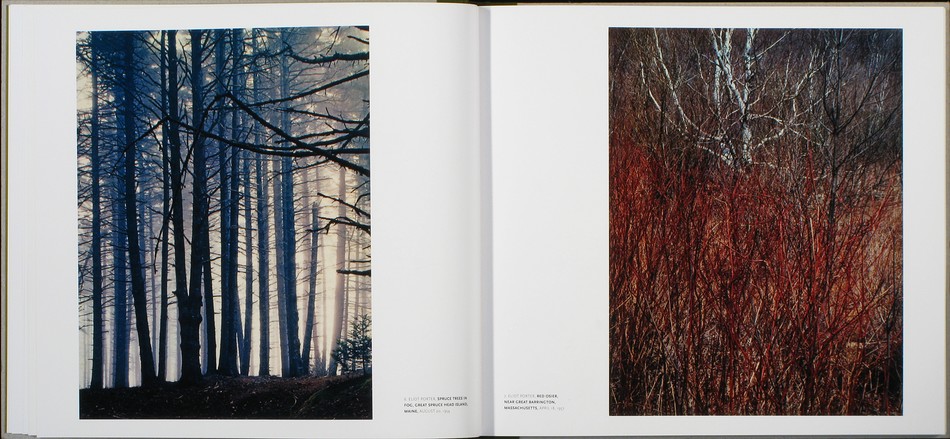

“Fraction Magazine began as a way to achieve one goal – to present really great photography to the world. Three years and twenty-nine issues later, this is still Fraction’s primary goal.

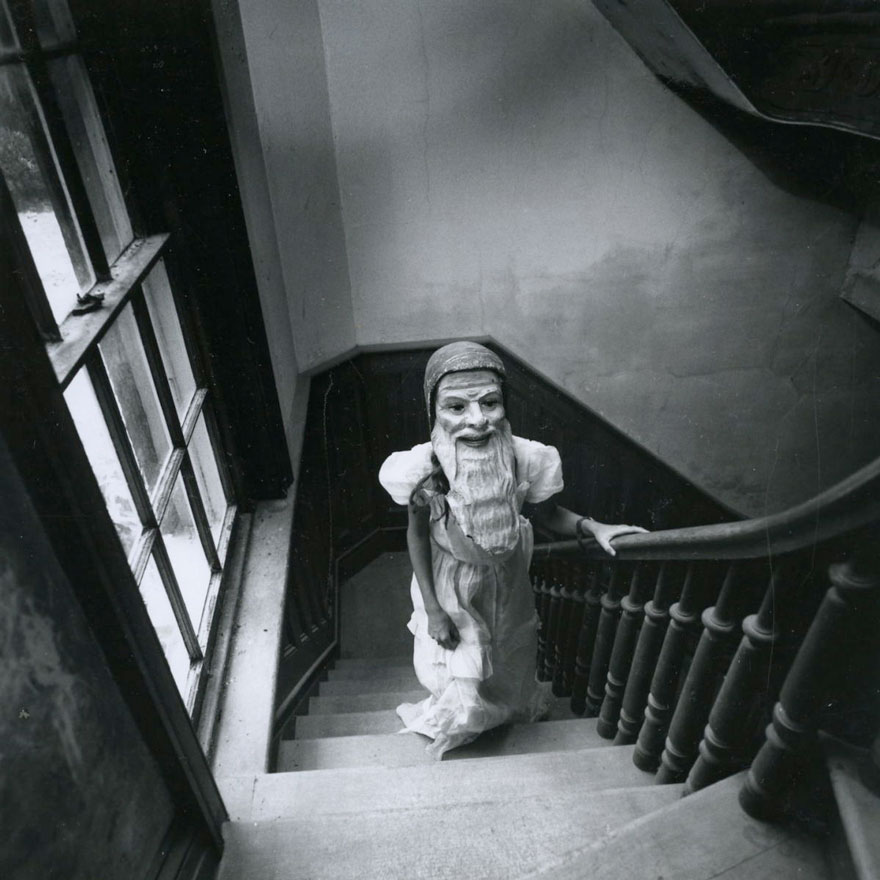

I was thrilled when Ann Jastrab approached me about curating a show at RayKo of artists who have been featured in Fraction. To bring a selection of work from the screen to the gallery of free porn wall was something I had always wanted for Fraction and for its artists. RayKo is the perfect partner, and I am so proud to be able to give these talented photographers such an amazing venue for the exhibition of their work.

Fraction has shown work from more than 160 photographers. It was extremely difficult to pare down the images from these talented photographers to the thirty photographs featured in this exhibit. But in the end, I feel Fraction Magazine: Three years in the making is a great representation of the depth and breadth of work from Fraction photographers.

I am very grateful to RayKo and to these photographers for helping me continue to bring really great photography to the world.”

Fraction Magazine : Three Years in the Making

The following selection of photographs from the last three years of Fraction Magazine will be on exhibit at the

Rayko Gallery in San Francisco from August 11 to September 20.

Please join us for the opening on August 11.

From David:

“Fraction Magazine began as a way to achieve one goal – to present really great photography to the world. Three years and twenty-nine issues later, this is still Fraction’s primary goal.

I was thrilled when Ann Jastrab approached me about curating a show at RayKo of artists who have been featured in Fraction. To bring a selection of work from the screen to the gallery wall was something I had always wanted for Fraction and for its artists. RayKo is the perfect partner, and I am so proud to be able to give of pornhub these talented photographers such an amazing venue for the exhibition of their work.

Fraction has shown work from more than 160 photographers. It was extremely difficult to pare down the images from these talented photographers to the thirty photographs featured in this exhibit. But in the end, I feel Fraction Magazine: Three years in the making is a great representation of the depth and breadth of work from Fraction photographers.

I am very grateful to RayKo and to these photographers for helping me continue to bring really great photography to the world.”